Roleplaying without dungeoncrawling is like eating noodles without salt. You can do it, but it's better with. So at one point or another you delve into the depths, to uncover some magical artifact, find some information or just for the thrill of exploring.

Designing a good dungeon takes time, maybe even multiple iterations, however. Or you take one of the many, many premade dungeons (or even adventures) and run that. As a solo player you don't have that luxury. You want to have a similar sense of wonder and excitement, when you don't know what lies behind the next corner.

Online dungeon generators are fine, but often they just do not fit the narrative you need at the moment. And maybe you don't have always internet access, wherever you play. There are also many iterations of random tables you can find in various books. But similarly they lack a cohesive structure.

I constructed a system that is a mixture of Perilous Wilds, Ironsworn: Delve and a little bit from Sundered Isles. It is my take on generating dungeons, as such I add to the plethora of resources out there - for the better or worse.

Laying the Foundation

In this section we lay the groundwork of our new dungeon. Setting the scene so to speak. The procedure in Perilous Wilds, does a pretty good job. I rearranged it a little bit but the core follows these four steps.

- Size it

- Stage it

- Name it

Size It

First up we determine the size of our new dungeon. We do not measure a dungeon by the amount of rooms, but by the amount of Landmarks (see Landmark, Hidden, Secret - it can be applied in so many places). It is an abstract representation of your journey through the dungeon.

| 1d12 | Size | Landmarks | Themes | Rank |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1-2 | Small | 1d6+1 | 2 | Easy |

| 3-6 | Medium | 1d8+7 | 3 | Normal |

| 7-9 | Large | 1d10+15 | 4 | Hard |

| 10-11 | Huge | 1d12+25 | 5 | Extreme |

| 12 | Megadungeon | 1d4+1 interconnected dungeons | - | - |

Similar to the setup of a new province, you outline the amount of landmarks on a hexgrid. Again this is not the real shape of the dungeon, but an abstract representation of it.

You will also notice, that with each size comes a rank. Each dungeon has a mystery (this idea is borrowed from Sundered Isles). Why was the dungeon built? What are its secrets? It is a progress that is filled as you go through the dungeon.

Stage It

Next up, you determine themes for the dungeon. Small tags or aspects. The amount of these themes is again determined by the dungeons size. These will help you, once you need inspiration on what you might find. Refer back to these themes.

A theme of nature or growth might mean, that the dungeon is overgrown with vines and plants. Some of them might be even hostile? Maybe poisonous?

Another thing is to figure out, what you might encounter in the dungeon. You can setup an encounter table as a start. Either fill it out now, or as you go. The entries should correspond to your themes. Nature will give you different encounters than necromancy for example.

You can also introduce different factions - especially in bigger dungeons. They can have separate slots in the encounter table as well.

Name It

A good dungeon should have a name. So give it one.

Plumping the depths

Progressing in the dungeon is pretty simple. You don't even need to be a good artist and draw an elaborate map. All you need to be able to draw is circles, triangles, square and some lines. I took inspiration from this article.

Choose any of the hexes in your dungeon to start, mark it with a small E, then roll on the landmark table below.

As you progress through the dungeon you then follow these rules:

- You can move to any adjacent hex from your current one, if it is within the boundary of the dungeon

- If the new hex is unexplored (i.e. it is empty), roll on the landmark table, then connect the two hexes (this new one and the one you left) together with a line

Landmarks

These are the possible landmarks you can encounter. Roll 2d6. The first gives you the type of the landmark: Feature, Danger or Opportunity. The second one gives you more details for this type. Whenever you need inspiration on how to interpret these, look at your themes and how you staged the dungeon.

| 1d6 | Landmark | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 1-2 | Feature (Circle) |

Roll 1d6 1 Dead End 2-3 Shortcut 4-6 Sight |

| 3-4 | Danger (Triangle) |

Roll 1d6 1 Hazard / Obstacle 2 Trap 3-6 Encounter |

| 5-6 | Opportunity (Square) |

Roll 1d6 1-3 Cipher 4-5 Treasure 6 NPC |

Most of these things should be self-explanatory, for some I go a bit into detail though.

Trap (Danger)

This is pretty obvious what it is, but I want to give some context around it. Encountering this landmark doesn't necessarily mean, that you trigger the trap immediately. It could. This just means that you find a trap at this point. Depending on a dice roll (like Perception or Find Trap) it determines if you actually found the trap by triggering it, or if you saw it before.

A sprung trap also doesn't mean direct harm to your character. It is just a different situation they have to get out of. Either dodging it or finding another solution.

Cipher (Opportunity)

Remember during the Size It step, we created a mystery for the dungeon? The cipher is a the way you can actually progress that track. Whenever you find a cipher increase the score of the progress.

Once you finished your dungeon (i.e. you found all rooms), you may come up with a theory on what the solution to the mystery is and conclude it. If you fail, you need to gather more information and create a new theory. You might find more information about the dungeon outside (thus providing you with another thread). You do not have to solve the mystery. Some secrets should remain.

You can give the cipher also some flavour by rolling on this table.

| 1d8 | Cipher |

|---|---|

| 1 | Carved Glyphs |

| 2 | Strange Markings |

| 3 | Map or Document |

| 4 | Murals, Statues or other artwork |

| 5 | Unusual Architecture |

| 6 | Remains |

| 7 | Memento |

| 8 | Puzzle or Key |

Shortcut (Feature)

Normally you only connect two hexes, when one of them was unexplored. This basically represents your way through the dungeon. The shortcut gives you the opportunity to connect two hexes together that you already explored. These are like the shortcuts in Soulslike games.

Select another hex that is adjacent with your current one and that is explored and connect these two together. In the case you can't, but there is an unexplored hex adjacent, you found a secret passage to that unexplored hex. If you still can't, then it is a dead end.

Sight (Feature)

These are your quintessential empty rooms. Some opportunity to add some set dressing to your dungeon and enforce the themes. Maybe a random encounter will take place here though...

Tension Pool

Progressing through the dungeon will also tick the tension pool. Moving from one landmark to another (regardless if it is explored or not) is a time-consuming action.

The complication table for a dungeon may look something like this.

| d12 | Complication | Effect |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Exhaustion | Gain Fatigue |

| 2-3 | Environment | Obstruction, Hazard, ... |

| 4-6 | Expiration | Torch / Light goes out (or reduces in use) |

| 7-9 | Setback | Random Encounter |

| 10-11 | Sign | Cipher |

| 12 | Advantage | Nothing happens |

Dungeons, Caves and Lairs

I differentiate between these three things. In my opinion they each serve their own purpose.

Lairs have a very limited scope - one or two "rooms". They house a single monster or monster (basically one specific encounter). Dwellings are very similar to lairs, but in contrast they tend to house humanoids (or generally people). You won't need special dungeoncrawling rules for this. You can just run it as a few scenes and be done with it.

Caves are a bit bigger in scope than lairs. There may be more than one occupant, but at maximum two. Occupants are of a specific type (like Orcs or Goblins), but can vary within that type. So you might encounter Goblin Shamans, Goblin Warriors etc. Caves are generally found underground and its environment doesn't change much. You can run this as small or medium dungeons, but remove the mystery from it (treat Cipher as just another empty room).

Lastly we have the dungeons itself, which is what these rules are for. These are your complex structures. Spanning many rooms, changing environments and a wide variety of factions that live therein. Dungeons are built for specific purposes (whereas caves for example are mostly changed to fit a purpose).

Megadungeons

I glossed over on how you actually do megadungeons. To be honest, I have to come up with more elaborate rules for them in the future, but for now, there are a few tweaks you can do to the existing procedure.

In the Size It step you basically create multiple dungeons. Roll again (this time with a d10 instead of a d12) to determine the size of the other dungeons (and follow all the other steps as well). You then select one of them to start with.

Adjust the landmark table a little bit. Change the feature landmark to read the following

| Landmark |

|---|

| Roll 1d6 1 Dead End 2-3 Shortcut 4-5 Sight 6 Connector |

The connector is a path to one of the other dungeons (roll to see which one). Then continue your exploring.

In the rare case you can't find a connector in your first dungeon (or on any other one), there are two possibilities: There's another entrance on the outside or the connector is hidden. In the latter case you could then roll to see if you find such a connector (it was hidden).

Note, that since you create separate dungeons, that each has their own themes, encounter table and mystery.

Example

Pictures sometimes say more than a thousand words.

As you can see, it is a very small and simple dungeon. Just six rooms. From the numbering you can guess the path I took through it and what I found.

During the exploration I also filled my Tension Pool once (this should naturally happen at least every 6th landmark). I was lucky and rolled a 10 on my complication die and got another cipher - so my actual progress on the mystery should be 8.

Maybe the NPC that I "rescued" from the dungeon has more to tell me?

Why a hexgrid?

Essentially we have a pointcrawl. So why do I introduce a hexgrid? And boundaries? Before you fetch your pitchforks, let me explain. It will (hopefully) make sense. I will actually split the question into two: Why hexagons? Why a grid?

To answer the first question: hexagons are the bestagons. That's it. End of story.

Well it also has some practical reasons behind it. Why not squares? After all, dungeon rooms normally tend to be square as well, so this would feel more natural.

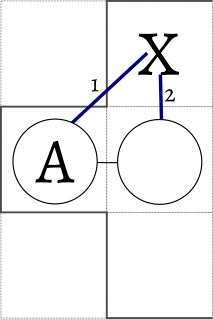

The problem arises with diagonals. Not so much, that you cover more space (because of Pythagoras and stuff). Since we are working with abstract distances anyway, that's not so much of a problem. What is a problem though, is when you get into a "dead-end" situation. In the above situation, would you allow crossing the boundaries to get to X directly from A? Or do you have to go back?

With hexagons, this situation does not happen. Of course you can set yourself some ground rules and be totally fine with square grids as well. I'd rather just use hexagons.

For the matter on why to use a grid.

The first key point with the grid is the boundary you draw when you determine the size of the dungeon. Visually you can see, if there's still more to explore in the dungeon or not. You don't have to count the already explored areas over and over again. This makes it very quick to actually play a dungeon.

Second, it also alleviates the problem a bit, that you just create linear dungeons. Which is something that I ended up doing a lot in Ironsworn: Delve. At some point you will end up with a Tron Ligh-Cycle issue, where your trail will end up in a dead end. So you organically go back and branch your path. Shortcuts also help with avoiding linear dungeons.

You don't strictly need a hexgrid (or any grid at all), but it is so much simpler to just use one.